Apps in both Google Play and the Apple App Store frequently send users' highly personal information to third parties, often with little or no notice, according to recently published research that studied 110 apps.

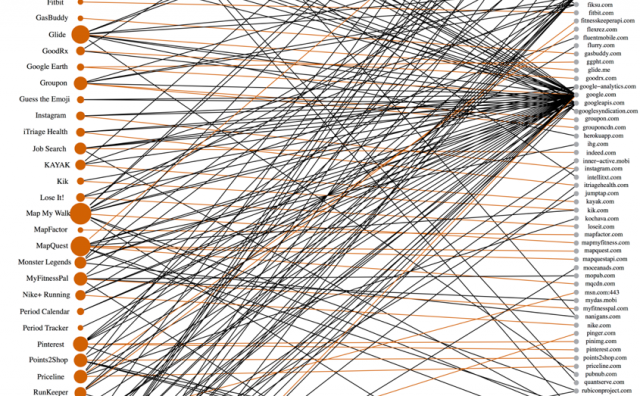

The researchers analyzed 55 of the most popular apps from each market and found that a significant percentage of them regularly provided Google, Apple, and other third parties with user e-mail addresses, names, and physical locations. On average, Android apps sent potentially sensitive data to 3.1 third-party domains while the average iOS app sent it to 2.6 third-party domains. In some cases, health apps sent searches including words such as "herpes" and "interferon" to no fewer than five domains with no notification that it was happening.

"The results of this study point out that the current permissions systems on iOS and Android are limited in how comprehensively they inform users about the degree of data sharing that occurs," the authors of the study, titled Who Knows What About Me? A Survey of Behind the Scenes Personal Data Sharing to Third Parties by Mobile Apps, wrote. "Apps on Android and iOS today do not need to have permission request notifications for user inputs like PII and behavioral data."

The personal information most commonly transmitted by Android apps was a user's e-mail address, with 73 percent of the apps studied sending that data. In total, 49 percent of Android apps sent users' names, 33 percent transmitted users' current GPS coordinates, 25 percent sent addresses, and 24 percent sent a phone's IMEI or other details. An app from Drugs.com, meanwhile, sent the medical search terms "herpes" and "interferon" to five domains, including doubleclick.net, googlesyndication.com, intellitxt.com, quantserve.com, and scorecardresearch.com, although those domains didn't receive other personal information.

Also concerning were Android apps that sent third parties potentially sensitive combinations of data. Facebook, for example, received users' names and locations from seven of the apps analyzed in the study—American Well, Groupon, Pinterest, RunKeeper, Tango, Text Free, and Timehop. The domain Appboy.com received the data from an app called Glide.

The researchers also noticed that 51 of the 55 Android apps tested connected to the domain safemovedm.com. The researchers wrote:

The purpose of this domain connection is unclear at this time; however, its ubiquity is curious. When we used the phone without running any app, connections to this domain continued. It may be a background connection being made by the Android operating system; thus we excluded it from the tables and figures in order to avoid mis-attributing this connection to the apps we tested. The relative emptiness of the information flows sent to safemovedm.com indicate the possibility of communication via other ports outside of HTTP not captured by mitmproxy.

A Google spokeswoman contacted for this post didn't provide any information about safemovedm.com or say why the Android operating system would connect to it. Web searches provided a variety of theories about the purpose of Android connections to the domain.

iOS apps, meanwhile, most often sent third parties a user's current location, with 47 percent of apps analyzed in the study transmitting such data. In total, 18 percent of apps sent names, and 16 percent of apps sent e-mail addresses. The Pinterest app sent names to four third-party domains, including yoz.io.facebook.com, crittercism.com, and flurry.com.

Several of the apps in the study sent other sensitive information. For instance, Period Tracker Lite, an app that tracks menstrual cycles, transmitted symptom inputs such as "insomnia" with apsalar.com, while job-search apps from Indeed.com and Snagajob shared employment-related inputs such as "nurse" and "car mechanic" with four domains, including 207.net, healthcareresource.com, google-analytics.com, and scorecardresearch.com.

One thing app users can do to safeguard their personal information, the researchers suggest, is to supply false data when possible to app requests. The researchers also said that apps can be redesigned to allow users to opt out of data collection and that app stores could more prominently inform users about third parties who may receive their data.