The Next Social Media We Want and Need! — Backchannel — Medium

Save article ToRead Archive Delete · Log in Log out

14 min read · View original · medium.com/backchannel

The Next Social Media We Want and Need!

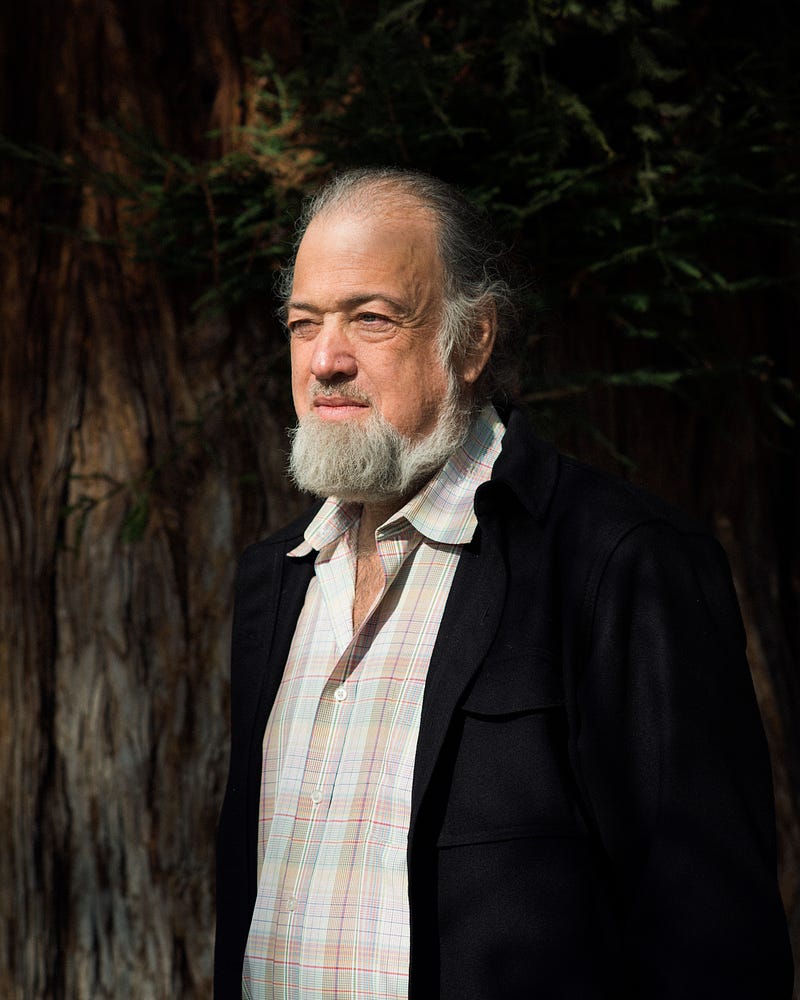

Crypto giant David Chaum explains his PrivaTegrity, and tells why it’s so vital

Editor’s note: I first met David Chaum in 1994, while writing a story about digital money for Wired Magazine, and he became a key source and subject for my 2001 book, Crypto. He emerged in the news this month as the inventor of PrivaTegrity, a new social media system. His proposal drew a lot of attention and some strong criticism from some sectors of the security community. Since I have always known David as one of the fiercest advocates of privacy I’ve ever met, as well as someone exceedingly skeptical of government encroachment, I encouraged him to explain his ideas here on Backchannel, in his own words. –Steven Levy

By David Chaum

In the rush to build out the web, it was structured around concepts taken from paper-based media. Now, many feel a strong need for a next level of security and privacy, a level that cannot be provided by such structures. What’s at stake is not only the future of social media, but that of democracy itself.

Last week, while preparing a lecture, I searched quickly for some charts showing survey results for social media usage and privacy. The huge mismatch between what people want and what they are getting today was stunning. Social media I learned are used mainly for communicating with relatives and close friends with the next most significant use relating to political discourse. Yet social media was at the bottom of the trust rankings, with only 2 percent confidence. About 70 percent of respondents said they are very concerned about privacy and protection of their data.

Today’s social-media, as McLuhan said is always the case, initially copied the old media, but will next realize its full potential [The Essential Marshall McLuhan, (1995), Eric McLuhan & Frank Zingrone eds. Don Mills, ON. ISBN-13: 978–0465019953]. This also resonates with what Maslow told us, people focus on the current need level until it is met (in this case basic social-media functionality) and only then switch focus to a new need defining the next level up (protecting informational self-determination). Technology permitting, a next level would seem inevitable.

If only this next level were merely a nice-to-have. Classical Athens created the main ingredients of Western civilization, from the sciences to the arts, arguably enabled by their democracy. Our own constitutions, like theirs, provide the mechanism of governance, which by all accounts is not enough to breathe life into democracy. The First Amendment to the US Constitution, albeit framed in the days of paper media, pretty much lays out the magic ingredient: people need justifiable confidence that their information and interactions are protected.

The explicit right to a free press it seems to me, though I’m no constitutional scholar, should translate today to an infrastructure not only for publishing information but for protecting those publishing, providing, or consuming it, as well as those financially supporting its publication. Just as the rights to speech, assembly, and petition should translate to online infrastructure in which discourse at all levels is protected and groups can meaningfully express their views (let alone the fourth amendment right to protection of your own information). With these essential rights, a democracy can function and use its mechanism of governance to create new rights and protections. Absent these essential rights, the mechanism of governance becomes hollow, lacks legitimacy, and most frighteningly is at best brittle in the face of rapid change.

Can a technology create the infrastructure needed for this next level of information protection? It’s admittedly awkward to have to say so, but I have devised a system myself that offers a solution. I call it PrivaTegrity. It is now not only feasible but even quite practical to implement a suitably-protected social media system that will acceptably match the performance of current unprotected systems.

How soon will such a secure and private infrastructure actually be available to most users? PrivaTegrity can stand alongside today’s leading social media systems, especially since many users are already on more than one, and gradually take its share of the social media pie. PrivaTegrity has low capital requirements, no barrier to going direct to consumers, and even a variety of revenue models — a dream opportunity for technology backers and investors. With vision and leadership, it is now a very real and actionable possibility.

There are two key concepts to understanding the new paradigm that meets the unmet need and can take us to the next level: (a) The difference between privacy of association and anonymous accounts; and (b) the untapped rich space of possibilities between the extremes of pure identification and pure anonymity.

Privacy of association is a good place to start. Probably the most useful tool for intelligence gathering, euphemistically called “meta data” in recent public discussion, has long been known in the spy trade as “traffic analysis.” It’s basis lies in observing all message traffic traveling on a network and discerning who’s communicating with whom, how much, and when. Snowden, whether hero or traitor, taught us another term of art, the “full take,” naming the practice he revealed of agencies around the world tapping (and sharing to avoid national prohibitions) all data on major fiber and other networks. This practice yields complete visibility of what is in effect the sender and recipient addresses on, as well as the amount of content weight of, all the envelopes that carry all data, including chat, emails, and web interactions. (The strategy seems to be archive everything in case traffic analysis finds something worth going back and reading.)

Privacy of association is simply protection against traffic analysis. Illustrative is the discrete little cafe you frequent to enjoy a kind of separate life of surprisingly intimate conversations with people you otherwise don’t know. When you later discover video surveillance had been installed nearby, you suddenly realize that who visits that cafe, exactly when, and for how long, has all been recorded — you had no privacy of association.

How can online services provide privacy of association? There is only one practical and effective way that I know of. Messages from users must be padded to be uniform in size and combined into relatively large “batches,” then shuffled by some trustworthy means, with the resulting items of the randomly ordered output batch then distributed to their respective destinations. (Technically, decryption needs to be included in the shuffling.) Shortcuts to this provide a honeypot trap for the unwary. For instance, any system that has varied message sizes, like web pages, no matter the choice of computers that messages are routed through, is transparent to traffic analysis with the full take; systems where the timing of messages is not hidden by large batches are similarly ineffective.

How can the shuffling of a batch of messages be performed fast enough while maintaining high security against anyone learning what particular re-arangement the shuffle carried out? The only way I know of is by dividing control among a series of motivated but independent and vetted shuffling entities (each also doing a portion of the decryption). In contexts where serious security is needed in the real world today — and now social media need not be the “trust us” and “back-door-available” exception — no single entity is allowed free reign. Two-man rule for nuclear weapons and power plants, dual controls in banking, external auditors in financial and many other systems. Once you get beyond two, the much weaker simple majority, or super majority for exceptional situations, is the rule. For example, five permanent members of the UN Security Council, nine supreme court judges, three-quarters of state legislatures to change the US Constitution. In cryptography, theoretical or commercial, keys are typically divided into “shares” with majority rule.

Users of PrivaTegrity would receive unprecedented security — enforced by unanimity of ten data centers. Compromise or collusion of any nine is useless in compromising privacy or changing data. Including too many more than ten would, on the one hand, start to slow response time unacceptably. On the other hand, weakening to less than unanimity is unnecessary (since pre-computation anticipating the unlikely failure of high-availability data centers allows cut-over without skipping a beat). Ten is also roughly a sweet spot relative to the number of democracies around the world with attractive data protection laws and digital infrastructure. Each contracting data center should implement their own heterogeneous security provisions, including data destruction and tamper-responding key boxes with irrevocable policy programed in, and at least one would likely sound the alarm if there were a concerted effort at compromise. Not only does this radically raise the bar on the kinds of systems that have been hacked to date, it similarly provides a never-before-seen and very much higher level of protection against governments spying or (another capability Snowden revealed) injecting false identities or false information.

Who gets to pick the data centers? I yield to the wisdom of the crowd on this. Let me propose that the choice be made by a vote of the users. Some countries are run by officials elected online, major corporations routinely hold remote stockholder votes. PrivaTegrity can, for the first time (as explained below), let you vote along with users from around the world. Such periodic votes would be informed by candidate data centers each posting their proposal, including such things as technical specs, track record, management team, and relevant law in their political jurisdiction. Candidate centers might also allow independent security audits, including of their code and physical protections, with posted findings. Users would each have an equal vote. I also concur with the wisdom of the crowd that data centers willing to cooperate in any kind of surveillance, if not voted out, would cause users to leave the system.

Anonymity of account, the other half of the privacy puzzle that remains once privacy of association has been solved, is easier. Solving one without the other, however, accomplishes nothing apart from creating a false sense of security — since either can allow tracing, they must both be solved simultaneously to actually give you privacy. PrivaTegrity does what no major service today does — it simultaneously provides both privacy of association and anonymity of account.

The numbered Swiss bank account concept exemplifies anonymity of account. The bank does not know the identity of its customers. The continuity of user relationships over time, however, should also not accumulate data that can link transactions to users. Traditional banks would typically have a lot of records related to your account, while PrivaTegrity’s anonymity of account avoids such vulnerability.

PrivaTegrity’s integrated payments facility has no accounts. Instead you own your coins by holding their respective keys (actually your phone does this on your behalf), which are validated online by tenfold controls. Another example of anonymity of account is PrivaTegrity’s chat system. The ten centers would have to conspire to determine which accounts you communicate with (or for that matter to insert man-in-the-middle back doors possible in existing systems), but none of your data are retained, and keys are changed at each step to protect previous communication.

Identification technology may seem a surprising desire of someone who works to advance privacy. Lack of identification infrastructure in my view, however, has impeded much needed protection. Today forums are flooded with spam and irresponsible posts. More significantly those intent on evil are essentially untraceable (causing an escalation of countermeasures and distrust), while the rest of us are easily tracked. It’s the worst of both worlds! PrivaTegrity has a unique option to provide infrastructure with a powerful way to leverage identification for the best of both worlds!

Identification has two polar opposite forms: perfect anonymity and perfect identification. The whole rich and very useful space between these, what in the mid 80’s I dubbed “limited anonymity,” still remains untapped in practice.

An example of limited anonymity, eCash was the first electronic currency (issued on my watch as founder and CEO of DigiCash by Deutsche Bank among others under license in the 90’s). When you made an eCash payment you handed over ownership of a “digital bearer instrument,” bits verifiable immediately online as good funds. It’s like handing someone a gold coin that they can instantly test for purity. Except that with eCash, the payer can later prove who received the money, but not the other way around. This protects the privacy of your purchases while making eCash unsuitable for what the Bank for International Settlement defined as criminal use: black markets, extortion and bribery. I often wonder how much better the world would be if paper money were replaced by such a limited-anonymity currency. PrivaTegrity realizes payer anonymity with a different mechanism (so light-weight in fact it could displace advertising by allowing people to anonymously pay tiny amounts for content they appreciate and want to support).

Another simple but useful example of limited anonymity is PrivaTegrity’s pairwise pseudonyms. You can always send a message under a pseudonym of your choice to a person, or to a public forum where your posts may be followed anonymously by many. You can also, instead, opt to send it with limited anonymity. For all such messages from you to that same address, the same pairwise system-generated pseudonym will be used. This pseudonym allows neither the system to link nor either party to identify the other. Such pairwise pseudonyms do, however, mean that everyone immediately recognize any comments you made on your own posts, and nobody can comment on posts under more than one pseudonym. Pairwise pseudonyms also mean in effect that your vote can be counted. (Voters can see their pseudonymous ballots in the published list and that the list is tallied correctly.)

Today we’re so used to being required to give all manner of identifying information for the privilege of having an “account” and “password.” We are assured this is for our own protection. But, if someone breaks into even any one of these systems “protecting” us, they can steal and widely abuse our identities. Such incidents are often reported. Moreover, the widespread use of various identifiers facilitates the widespread sharing of data, explaining, for instance, the often surprising knowledge online ads seem to have about us.

By contrast, to opt in to PrivaTegrity’s identification infrastructure you provide a different type of identification to each data center, each requesting only its own particular narrow specific type of ID. This infrastructure makes it very difficult for any one person to have more than one account, though someone breaking into a data center would not find enough to impersonate you elsewhere. If, however, you were to lose your phone and need to get your account running on a replacement, you simply provide the same information.

This high-integrity identification base allows PrivaTegrity to build the kind of infrastructure that I introduced in the 80’s as a “credential mechanism.” This mechanism turns the ID-based paradigm inside out. Your phone can use credential signatures it has received to prove that the answers to queries are correct, revealing neither your identity nor other details. As a real-world example, you can answer the following question: “Are you of drinking age and allowed to drive a car and have you paid your insurance and taxes?” without having to reveal your name, where you live, how old you actually are, or any other detail — the only information revealed is the indisputable truth of your “yes” answer. Credentials can also be a basis for a new type of reputation economy.

PrivaTegrity, in addition to the intriguing new options it gives, may soon provide all of us a place online that securely safeguards the very much wanted and necessary conditions of privacy for democracy.

Photographs by Nathanael Turner for Backchannel