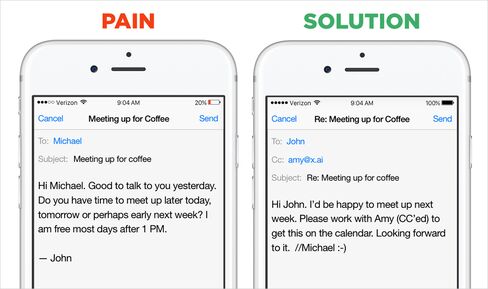

Amy Ingram, the artificial intelligence personal assistant from startup X.ai, sounds remarkably like a real person. The company designed her to take on the mundane tasks of scheduling meetings and e-mailing about appointments. If a bot had access to your calendar and was cc-ed on correspondence, why couldn’t it do the work for you? After she made her debut in 2014, users praised her “humanlike tone” and “eloquent manners.” “Actually better than a human for this task,” a beta tester tweeted. But what most people don't realize about this artificial intelligence is that it isn't totally artificial: Behind almost every e-mail is an actual human—someone like 24-year-old Willie Calvin.

Calvin, who worked as an AI trainer for X.ai before he said he quit in October, was part of the reason Amy never tripped up, sending the sort of blind response that reveals she’s a bot. The company advertises Amy as an AI personal assistant who can “magically schedule meetings,” and its software does scan e-mails and can usually guess that “tomorrow" means Tuesday. But the system isn’t yet ready to take the next step on its own. Multiple former AI trainers said that as recently as a few months ago, trainers looked over parts of almost all incoming e-mails — to evaluate what Amy guessed the user was saying— before Amy generated an auto response. A company spokeswoman said the service still has trainers verify “the vast majority” of information in e-mails so the system can improve.

Calvin joined X.ai in December 2014 just a few months after graduating from the University of Chicago with a public policy degree. He was under the impression that his $45,000 annual salary job as an AI trainer would be half product development and half reviewing the algorithm’s accuracy. He said he was asked, as part of the job application, to write a one-page essay on why automation would be good for jobs and workers. X.ai declined to comment on specific hiring practices.

He was excited at the chance to do product development at a tech startup, but once he started work, he said he found that the product part of the job never materialized. Instead, Calvin said he sometimes sat in front of a computer for 12 hours a day, clicking and highlighting phrases. “It was either really boring or incredibly frustrating,” he said. “It was a weird combination of the exact same thing over and over again and really frustrating single cases of a person demanding something we couldn’t provide.” Kristal Bergfield, who oversees X.ai’s trainers, said that that the job has evolved over time and entails hard work. “We’re building something that’s entirely new,” she said. “It’s an incredibly ambitious thing, and so are the people who work here.”

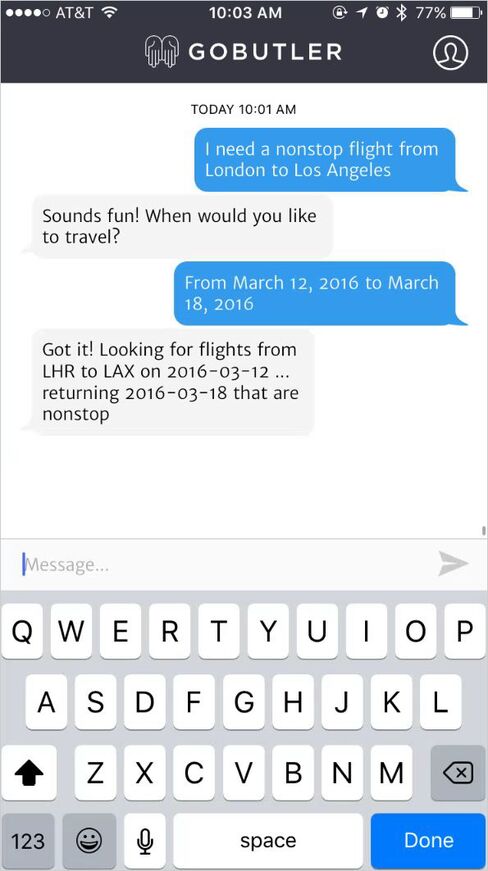

A handful of companies employ humans pretending to be robots pretending to be humans. In the past two years, companies offering do-anything concierges (Magic, Facebook’s M, GoButler); shopping assistants (Operator, Mezi); and e-mail schedulers (X.ai, Clara) have sprung up. The goal for most of these businesses is to require as few humans as possible. People are expensive. They don’t scale. They need health insurance. But for now, the companies are largely powered by people, clicking behind the curtain and making it look like magic.

The incentive to play up automation is high. Human-assisted AI is “the hottest space to be in right now,” said Navid Hadzaad, who founded bot-and-human concierge service GoButler. Startups in this arena have together raised at least $50 million in venture capital funding in the past two years. But companies with a wide variety of strategies all use similar and vague marketing language and don’t often divulge operational details.

Facebook turned the spotlight on human-assisted AI last summer when it introduced M, a chirpy personal assistant bot that lives in Messenger, its chat app. Unlike Facebook’s all-automated commercial Messenger bots, all of M’s AI-generated responses are reviewed, edited if necessary and sent out by a team of a few dozen contractors, who work out of the social network’s Menlo Park, Calif., campus, the company said. Beyond that, details on M are sparse: Facebook won’t say what hours the contractors work or how often they correct M’s guesses.

Clara, which offers an e-mail scheduling service similar to X.ai’s, uses contractors to review some e-mails. Maran Nelson, the chief executive officer, said most of the workers are women but won’t say how many there are, where they work, or what percentage of e-mails are looked at by a person.

“That’s a common frustration among anybody in this category—how opaque it is,” said Nelson. “It was similarly frustrating when Clara was three months old to have a lot of investors congratulate us on having a fully automated bot.”

It’s often a messy process to mimic a computer’s superhuman abilities. At X.ai, Calvin said there were some days in early 2015 when trainers started annotating e-mails at 7 a.m. and had to stay until 9:30 p.m., because the service was supposed to be close to 24/7, and they couldn’t leave until the queue of e-mails was done for the night. “I left feeling totally numb and absent of any sort of emotion,” Calvin said. The company wouldn't comment on the schedules of its current 21 AI trainers, but Bergfield said: “We would never tell people that they need to work those hours.”

The same pace played out at GoButler, a we’ll-do-anything SMS-based concierge service in New York City. Customers would text in requests for such things as takeout meals and last-minute gifts, and employees like Lucy Pichardo would see the request come in through an interface powered by customer-service dashboard Zendesk. She would then turn around and place the order online through another service, such as Postmates or Seamless.

GoButler’s website said the service uses human-assisted AI to fulfill customer requests 24/7, and Pichardo said customers constantly asked her if she was a robot. But she and another former employee, Alex Gioiella, said the only automated part of the service they saw was the occasional marketing text message. That meant humans had to be on duty at all times. GoButler’s workers, who were called Heroes, worked shifts from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. or 4 p.m. to midnight and for one week a month switched to the midnight to 8 a.m. shift, swapping places at shared desks in the company’s New York City office with those leaving from the previous shift. They were required to eat lunch at their desks and, last December, attended the office holiday party in 30-minute shifts so as not to have too many people away from their computers at once, Pichardo said. A spokeswoman said the company’s leadership team also took turns working Hero shifts during the holiday party.

"People felt a bit overworked and underappreciated,” said Gioiella, a former senior operations associate—also known as a Superhero. Heroes usually handled up to five requests at once, but when volume spiked, they might be juggling twice that. Gioiella said she tried to stall certain orders to gain a little extra time for her workers to get through the workload. One former Hero said they saw occasional requests—such as one for an antique human skull—that got them excited about solving a weird challenge. But usually, the Hero said, the requests were for pizza or Chipotle delivery.

Some people might find it unnerving to message a bot only to realize it’s a human. And the blur between man and machine can prompt unusual exchanges. One former trainer at X.ai, who is not authorized to talk about proprietary job details, estimated that people e-mailed Amy asking for sexual favors seven to 10 times a month. Other users would blame their own scheduling mistakes on Amy.

After a while, the X.ai trainers said they came to think of Amy almost as a real person. The team referred to her as a child because the service often made simple mistakes but, over time, would noticeably learn and improve, the trainer said. They wanted to protect her from bad data.

The two scheduling e-mail bot companies have divergent plans for expansion. Clara, which is slowly letting people off its waitlist and said it currently serves hundreds of companies, charges $199 per month per user. X.ai, on the other hand, plans to move from limited beta to a public release later this year and wants to charge about $9 per month. Dennis Mortensen, its founder, wrote in an e-mail that “only a machine-powered agent can take on the 10 billion formal meetings that U.S. knowledge workers schedule every year.” Mortensen said the service will start asking e-mail senders to clarify when the computer can’t interpret an message—“Did you mean Monday, April 4?”—instead of having an employee read it and infer. “We want to give the job away for free, or for $9, which you can only do if it’s software,” he said.

Nelson, Clara’s CEO, said she’d rather build a service that's more expensive and involves humans if that's what it takes to handle the task of scheduling reliably.

Other services are looking to move away from humans. At GoButler, the transition was abrupt. In February, GoButler gave its 25 Heroes pink slips. The company said it would be fully automated, concentrating first on flight bookings. Gioiella, the former operations manager, said she was often told that the company was running out of money and said she thought GoButler simply couldn’t afford to keep paying its staff. Spokeswoman Bianca McLaren said the company wasn’t in financial trouble but said that “our margins are a lot better now because we don’t have as many staff members.”

The specter of job loss hangs over much of the debate about artificial intelligence. But at least for some of these workers, training a robot replacement was never attractive for the long term. X.ai said four or five of its current 64 employees started as trainers and moved up, but Calvin said the stepping stone wasn’t worth it to him. “The work just ended up being way too taxing without a tangible payoff in sight,” he said. Or, as another former X.ai trainer put it, he wasn’t worried about his job being replaced by a bot. It was so boring he was actually looking forward to not having to do it anymore.