Technical Debt: Rescuing Legacy Code through Refactoring

Save article ToRead Archive Delete · Log in Log out

17 min read · View original · sitepoint.com

How can you get a legacy codebase under control and bring it to a new level of maturity? In this post, Jeroen summarizes the lessons learned from years of working on a large legacy web application. This article was originally published by intracto.

Legacy Code Can Be Saved by Refactoring

I have good news for you! Squirrels plant thousands of new trees every year by simply forgetting where they leave their acorns. Also: your project can be saved.

No matter how awful a muddy legacy code mess your boss has bravely volunteered for you to deal with, there is a way out of the mire. There will be twists and turns along the way, and a monster behind every other tree. But, one step at a time, you will get there.

Fear no evil

Fair enough, you didn’t ask for this horrific quest. The blood-covered ‘Here Be Dragons’ sign near the entrance of the code swamp induces a strong urge to call in sick for the next couple of years. At first glance, you’d rather have some light lunch first, and perhaps a leisurely stroll through the meadow after that, than being the petrified peasant to rid said swamp of its monsters.

Unfortunately though, you are forced past the sign by a galant yet firm nudge from the boss, who will stay behind to defend the town and in the process have some light lunch with the duke owning the swamp.

Bar some drastic measures, you can’t change these basic facts. However, you can turn a swamp into a magnificent meadow with just one muddy patch where cows live!

Technical Debt: How Did It Get This Way?

As you poke and prod the area just past the warning sign with a stick, you might wonder: how on earth can anyone have let this happen? Someone must have seen this coming, surely? Were the people who wrote this code that incompetent?

Possibly. But not more so than anyone else. When push comes to shove, however confident people might seem, nobody else knows what they’re doing either.

Incompetence is far from the whole story. The principle at work here is usually referred to with a metaphor: Technical Debt.

Code cancer

The idea is that during development of any project, shortcuts will be taken. Ugly hacks will be allowed to get ahead quickly, just this once. This way, a debt is accumulated: code that does the job any way it can but is completely incapable of being maintained properly, let alone built upon.

And so, bit by bit, a project’s code is corrupted. Nobody cares about this as long as they’re not the one having to touch it. But eventually someone has to, and it will probably be you.

This principle is at work in any project, and if it isn’t it most likely means you’re not moving fast enough. Your competition will take shortcuts, getting new features out more quickly. As a result, your precious users will leave, and join the party in the swamp next door and have a Long Island Iced Tea at the cocktail bar there instead of standing in your impeccable square meter meadow you’ve painstakingly created over the past year. Your meadow might be pretty in and of itself, but there’s just not much going on there.

So, any healthy project will accumulate some technical debt, but in order not to go bankrupt — the code getting so hard to maintain it becomes unmanageable — at some point this debt will have to be settled.

That is where the frightened and resentful peasant comes in, forced to pay the debt in the swamp owner’s stead. Paying this debt is often referred to as refactoring: swapping a bit of code with another bit that does exactly the same but can be maintained and expanded more easily.

Persuading the Customer

The duke, being the owner of the swamp, has a bit to say about which monsters you should be adding. There are always new features your customer wants to implement, the deadline for each one is last week and you should feel incompetent for not having finished all of them two weeks ago. So you will probably have a bit of explaining to do to convince him he needs to let you rebuild what he perceives as being in his possession already.

This is a critical point. If you don’t succeed in swaying your customer to start paying what he owes, technical debt will grow to the point of collapse. You will be the guy left in the rubble, held accountable.

In the end, your customer and you want exactly the same thing: have a fun and painless job that earns everyone involved a living. This follows from a stable project built from code you can change without the whole thing coming down on top of you.

Fight for your freedom

So for your own good, you need to make the situation clear. I think the best way to do it is to describe the impending doom lurking just around the corner, what the alternative is, and let the swamp owner know your good intentions:

- Explain what technical debt means, and how it makes development slow down to a halt if it gets too high. The customer has to realize in which ways this will cost him: time spent finding bugs, fixing them and creating new ones, insufficient time to add features and advance his business.

- Refactor with clear short-term goals in mind. You can add a new feature in a week, or you can refactor for a week and add it in a day, with the prospect of being able to add similar features in the future very easily. Show how option two will be more expensive short term but infinitely cheaper in the long term.

- Point out that you want the best for your customer and yourself, and that these two concerns are really the same thing.

Once you have the swamp owner on your side, the hardest part is over. You now have the freedom to move the project in the right direction.

A New Swamp Do Not Make

You can recover from a huge mess; don’t replace it with a new one. Greenfield rewrites seldom work out; most never get released.

When you finally convince the duke that people who stroll into his swamp consistently don’t come out again, he might want to build a new version. You might be tempted to comply, starting anew using shiny new tools, convinced everything will be better when you’re done. Don’t.

The main risks of a rewrite, as I see it, are:

- The Big Red Button Switch: the new code has never run in production before and is guaranteed to explode on first production use.

- Migration of data: exporting and importing data from the old system while keeping up with live data coming in is likely to go wrong.

- Mistakes old and new: while rewriting code, you will create bugs, recreate old bugs, miss subtleties and implicit features … Often these problems will occur in parts of the system that were not really problematic to begin with. You lose lots of time while not adding any value to the business of your customer.

- Keeping up with the business: during the long time you’re working on the new project, the old project needs to keep evolving with the business needs as well. The new code will need to rebuild the old features and add the new features continually being added to the old project.

So, don’t start over. Improve what you have.

Make Problems Visible

This might sound vaguely unpleasant, but the monsters in your swamp should be spitting in your face, dragons burning off the hairs on your arms, the gnome living near the mushroom-shaped rock kicking you in the shins.

These nuisances are in there ruining your project, whether you notice them or not. You need to face them in order to get rid of them. You need to be able to see what is going wrong at any point in time.

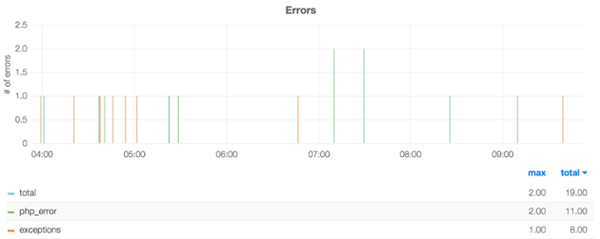

- Visualize errors: make some time every week to fix some of the errors that occur most often. Eventually the graph will flatline, hopefully beating you to it.

- Monitor your environment: this is critical in diagnosing bottlenecks and impending crises (see next paragraph).

Now you know where and when it hurts, enabling you to administer first aid instead of potentially spending all your time scratching itches on a dying man.

Fight What Hurts Most

Next, it is vital to have a vision of the system as it ought to be in a perfect world — a mental picture over your ultimate meadow guiding your every move:

Scratch it in the mud so you don’t forget. By taking small intermediate steps in the direction of heaven, you will find yourself looking through the fence eventually.

The key is now to take the information you get from your monitoring tools, and the yearning for Valhalla, combining the two to decide which problem to tackle first. Your biggest problem might not be a realistic goal right away, but start refactoring manageable roadblocks first and make your way there.

The cripple pixie that seems cross with you for some reason might annoy you, but she’s harmless. Your time is better spent contemplating how to kick the ogre out.

This Code Is Mine

Fixing problems that matter is essential, but this does not imply details do not matter. In fact, they are probably just as important.

The Boy Scout rule of keeping the camping ground cleaner than you found it is rule number one in the swamp survival guide. By continually cleaning up clutter, taking care not to leave new filth anywhere, your environment will get ever cleaner, until you find yourself in the pristine meadow you crave.

To achieve this, attitude is everything. Strive towards clean code.

- You have to care: the code is yours and anyone who touches it has to answer to you. Sloppiness and carelessness can not be tolerated.

- The whole team has to care: however much trouble you go through to clean up a project, if somebody undoes your hard work behind you, you’re getting nowhere.

- Discipline is of the essence: once you (or any team member!) start letting things slide, it will be next to impossible to escape.

- Keep taking small steps: in the right direction, of course. Progress is way more important than achieving perfection.

- Small victories generate momentum: you will start seeing really nice patches of code, inducing you to clean up adjacent patches as well.

Build a Library

A good indicator of civilization is the number of libraries per square meter. Therefore, to introduce civility into your project, this seems like an excellent approach.

Even the most treacherous morass will have, here and there, a few spots that aren’t too bad on their own. Whenever you find a bit of code that does a thing well, move it to your brand new library so it can be reused.

Doubtless, the code you’re expected to rescue will do things completely wrong. It will somehow completely ignore and circumvent any standards or best practices that would make your life as a developer easier. Nobody will fix this for you, there is only one way to go: start following these practices and standards in your new code.

Make available industry-standard components or modules and start using them. You will have code using old or custom ways to accomplish things, but that doesn’t mean you can’t build new stuff the proper way.

Refactor using your new tools

Once the tools are there, you can refactor existing code to use them as well. You don’t have to keep a marathon sprint to do this; just whenever you stumble upon a case that does things the old way, fix that case. Small steps. You will get to a point where everything is replaced and you won’t recognize the old code anymore.

Often, code would be quite acceptable, if it weren’t for the myriad dependencies scattered throughout (like session access, modules, or services consulted on the spot). A good way to handle this is by pushing these out of the method or function the code resides in, so they come in through the method’s parameters. That way, you make that bit of code self-contained and it becomes possible to move it around or split it up further.

And once code is self-contained, you can test it.

Building Confidence: Testing

A violent ogre roaming through the mud can do more damage than a violent ogre in chains. A great way to gain some control over your system is trying to put chains on the parts that are most critical and thus potentially cause the most damage — tests, preferably automated, that run on every build.

The more automated tests you have to check the behavior of the system, the more confidence you can have when changing things. Because, if anything breaks, your tests will tell you something is wrong so you can fix it before the problem makes it to the production environment.

High-level tests

One way to start testing your system is by adding acceptance tests for critical scenarios within your system. For an average e-commerce system, this would definitely include the checkout process: if no orders come in, you lose money. If orders come in but there’s a problem processing them, that’s something you can recover from without any customer noticing. With tests like that in place, you can protect yourself from unwittingly introducing major problems.

Low-level tests

On a lower level, you can apply unit tests. Using the small steps approach of pushing dependencies out of your methods one by one, the result will be code that has a clear input and a clear output. In this situation, it becomes possible to cover the functionality of that code using unit tests. You define a set of inputs and declare the outputs you expect your code to produce, and your test suite will make sure that bit of code keeps behaving as expected.

Don’t test everything

Testing every single line of code in a system is both economically unviable and unnecessary. In principle, it would be great to be perfectly confident about every aspect of your system, but the cost of making everything testable, writing tests and maintaining the tests will start to outweigh the benefits at some point. In my experience, your time is best spent writing tests for non-trivial business logic and parts of the system that would cause havoc should they malfunction (even if the code is actually simple).

In this way, you get the most dangerous monsters in chains and the swamp will be a safer, more predictable place for it.

Isolate and Replace

A useful technique that combines pretty much all of the strategic patterns listed above is the old ‘isolate-and-replace’.

Every once in a while, you will come across some code that is just intangible in its internal workings and effects to be properly small-steps refactored within polynomial time. In a case like this, consider the following approach:

- Isolate the messy part, drop it in a separate method or class.

- Push out dependencies so they come in as parameters.

- Split logic from side-effects (like saving to a DB) using a small-steps approach.

- Isolate the logic in a separate method.

- Add unit tests that cover the behavior of the logic.

- Rewrite the logic from scratch. If it passes the tests, it should at least be close to the behavior displayed by the old version.

- Run old and new version of the logic side by side in the production environment. The old version is still the one actually used.

- Log differences in output between the new and the old version.

- Monitor the logs diligently. Whenever a difference shows up, add a new unit test for that case and fix the new version to pass the new case.

- Repeat until old and new version consistently agree with each other.

- Switch the old version of the logic with the new version with confidence.

This technique allows you to swap a car’s motor without the car breaking down or it even noticing it had its internals replaced.

Persuading Yourself

The mindset and tools outlined above have proven, to me, to be a successful way of steering a system on the brink of collapse away from disaster.

Where initially I was hesitant of dedicating my efforts full time to the task of taking on a long-term legacy challenge, I now see the many ways in which it has contributed to me becoming a better developer:

- Learning to recognize bad code: you learn to see what’s bad because it’s what you have to spend most time on. The patterns you see here will not trip you up when you work on a new project because you know how it will hurt you in the future.

- Back to basics: in my case, every single aspect of the system had to be questioned and re-evaluated. Nothing is holy, and you get an appreciation for lots of issues modern day frameworks handle for you.

- You evolve with the system: you see new challenges arise as the system in your care grows. This way you learn which bottlenecks you need to deal with as more and more people use your work and you need to scale up to stay on top of things.

- People are generating shiny new legacy constantly: diligently, faster than they generate garbage belts in our oceans, knowing how to make it work is a good skill to have.

- Fun and rewarding: especially looking back on a road well traveled and realizing the system you have today looks nothing like the system you first met years ago induces a real sense of accomplishment.

To bring this substantial (or lengthy, at least) post to a close

You can be the frightened peasant tiptoeing through the swamp, hoping somebody will come find you and take you to Disneyland instead, or you can take matters into your own hands, act like you own the place and enforce your own rules. Any swamp has solid ground underneath, and you can find it.

Epilogue:

A few years later, you stroll through the meadow. On the horizon you can see the duke replacing the old ‘Here Be Dragons’ sign with a beer commercial.

He’s got a huge grin on his face.